We all have a place we love to go. For the artist Marina Karella it is a studio in the Northern Dodecanese in Chora, a hillside village on the island of Patmos built around the fortified monastery of St. John the Theologian. From a large courtyard that expands in different levels she overlooks the whitewashed neighboring rooftops and the deep nautical blue of the Aegean. Above the trees she can see the turreted outline of the castle-like monastery.

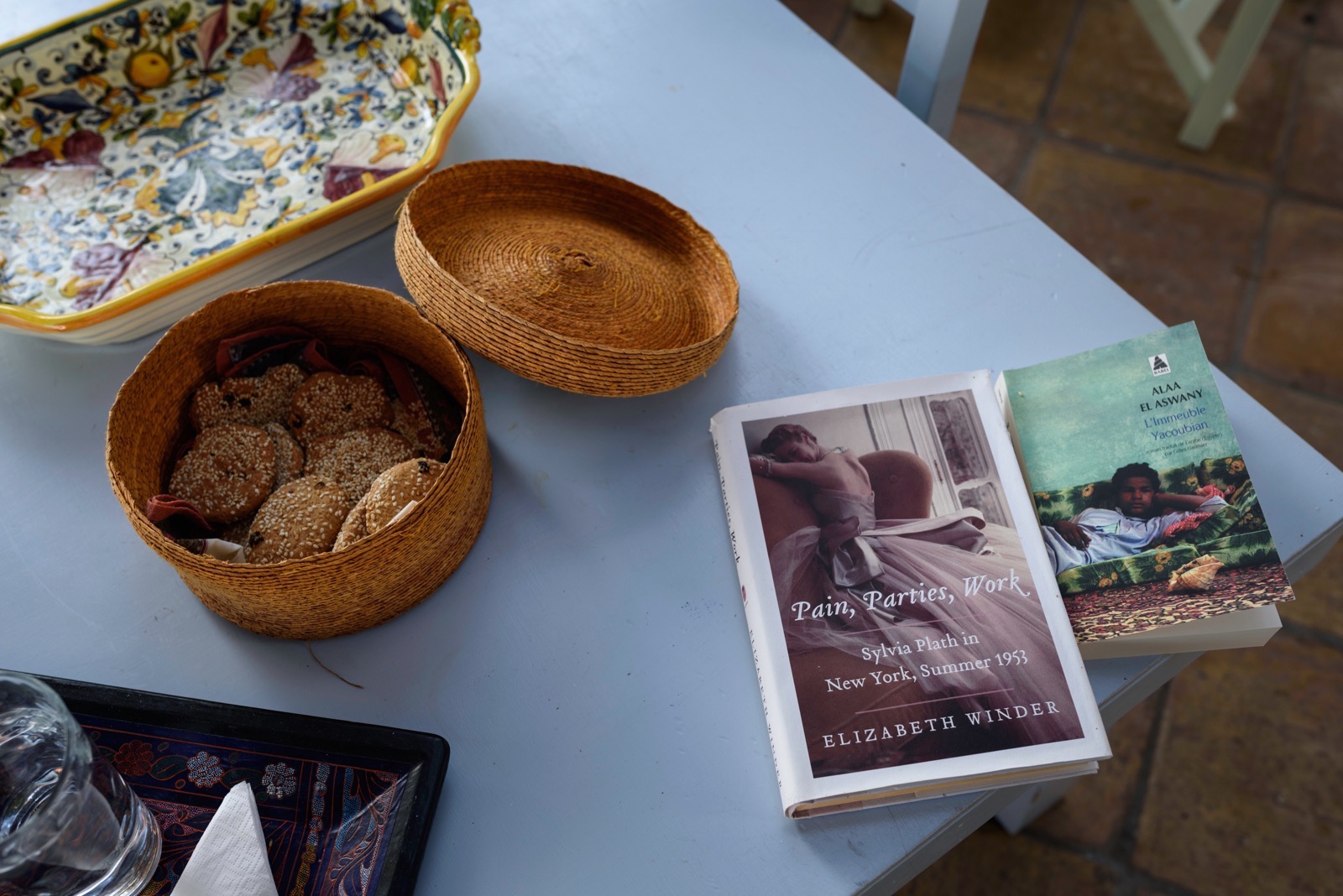

Invited to the island by a friend one year, she and Prince Michael of Greece, whom she married in 1965 at the Royal Palace in Athens, knew they wanted to remain and thirty years ago bought and rebuilt their house. On this August afternoon, a pine tree casts a comfortable shade on a sitting area where fresh figs, coffee and biscuits from a local bakery are served. There, her writer husband is reading the French edition of The Yacoubian Building by Alaa Al Aswany. “It has been a very prolific place. I work really well here and my husband adores it,” says Karella.

A wooden staircase leads down to her studio, a rectangular room with high ceilings illuminated by two large windows that overlook a flowering rhododendron and, as the faint sounds of passers-by reveal, a narrow street. Splashed with paint, the burgundy brick floor provides a contrast to the white walls and, seen from above, looks like an abstract expressionist painting. Karella’s desk is filled with saturated watercolor strokes and notes scribbled all over with a pencil. There also is the artist’s monograph. The frontispiece features the arrestingly beautiful black and white portrait of Karella by Robert Mapplethorpe that captures her poise and grace. Mapplethorpe was her friend. “A lovely person who had beautiful limpid eyes.” More photos of the artist follow after the portrait documenting moments with her husband, her mentor the Greek artist Yiannis Tsarouchis (one of the foremost Greek painters of the 20th century), and her two daughters. Together the photographs introduce her painting, sculpture and theatrical work.

On another table next to dozens of glass jars filled with different brushes — some pointed, some rounded, some square, and some looking like small fans — is the book Teachings of Rumi. “I love poetry. I did a whole show on W. H. Auden, about time.” She recites by heart a small verse that she finds particularly inspiring. “Time will say nothing but I told you so, / If Time only knows the price we have to pay; / If I could tell you I would let you know.”

Another favorite poet of hers is the Greek Constantine P. Cavafy. “A collector of mine commissioned me to do the portrait of Cavafy. One good day I woke up and I interpreted his poems.” She recites again, this time from Cavafy’s “Come Back.” in Greek: “Come back often and take hold of me, / sensation that I love come back and take hold of me”— “Really got into it. Can’t get out of him now. I might do some Cavafian furniture,” she says laughing.

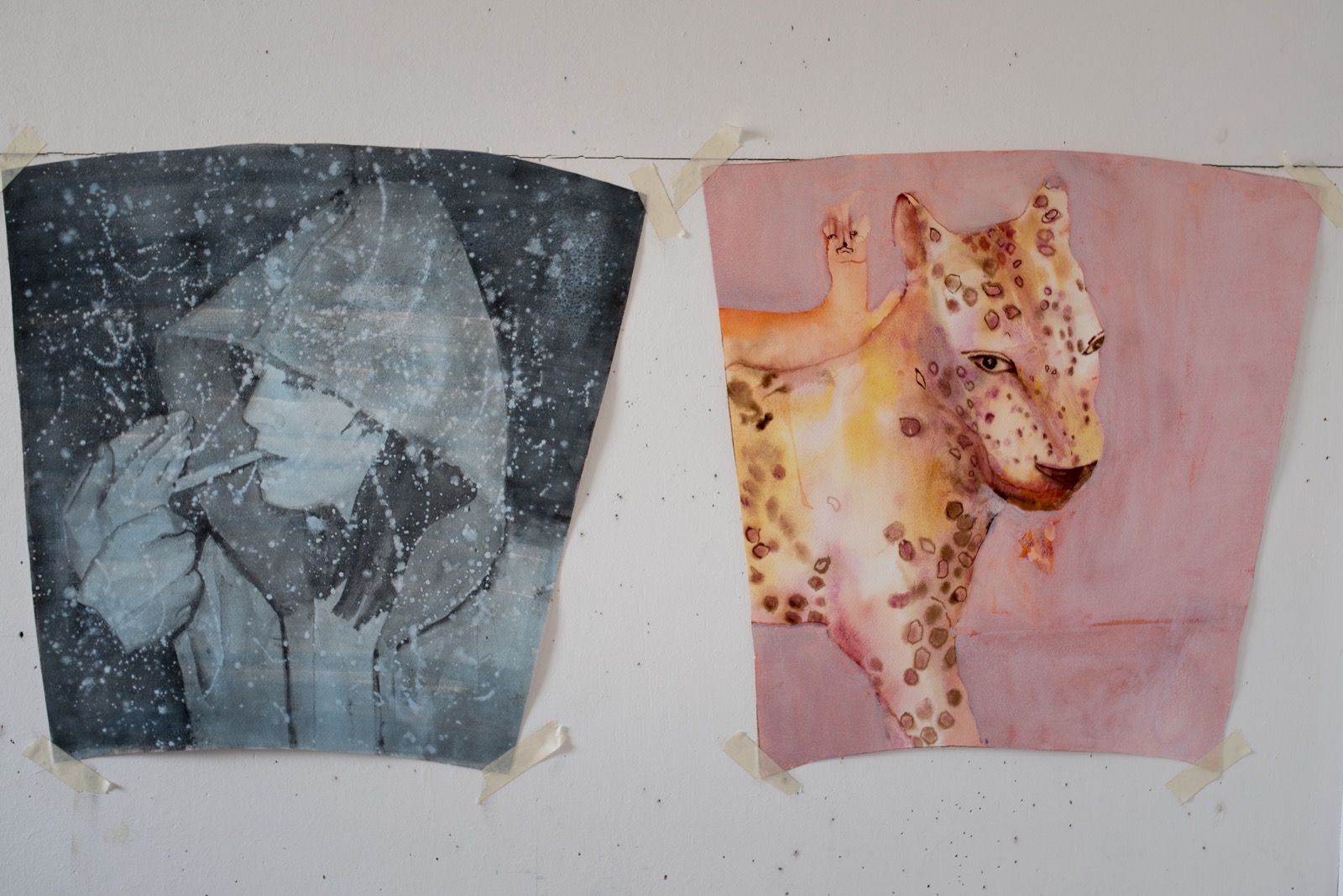

Against the white walls, her vibrant watercolor drawings bring life to an otherwise subdued and orderly space. One of them portrays a woman in a hooded jacket lighting up a cigarette. In black and white, it evokes her early monochromatic work. “When I first started, my idea was to make a totally white painting, but to be figurative. So I went as far as I could in that direction. I never could quite make it because you still had to see the image.” One has to look closely at her white oil paintings to decipher the shadows that give life to the figures floating in between the wrinkled fabrics. Like Antonio Corradini’s veiled marble statue Femme voile, Karella’s figures are sometimes entirely covered. Her famous White Boardswere shown at the Gallery Iolas in Paris in 1975. “When Iolas took me on, it was a celebration day. He would electrify everything. He would say, ‘Take it away. I don’t want to even see,’ and then he would say, ‘Thio! Heavenly! Fabulous! That’s the way to go.’ You felt that he had given you an adrenaline pill.”

Karella’s father, Greek industrialist Theodore Karellas, had always loved the impressionists, and his collection included paintings by Claude Monet and Armand Guillaumin. He used to say to her, “Marina put a tiny bit of color,” but she didn’t oblige. “I said ‘No I can’t, I can’t,’ and then he didn’t live to see that eventually I did put in color.” Colorful indeed are the paintings of a young boy, her grandson, with penetrating eyes in a sailor suit. “Those are done on Japanese paper. I want to stick it on wood and lacquer it on top.” The boy in the picture is a little younger than she was at the time she realized she wanted to become a painter. When she was 14 or 15, her eldest brother said he was going to show her work to Yannis Tsarouchis to see if he thought she could become an artist. “Tsarouchis said yes, so I didn’t have to say what I was going to do in life. I just knew.”

Karella’s little sailor echoes Tsarouchis’s portraits of Greek sailors, one of that artist’s preferred subjects. When she was sixteen, she started working with Tsarouchis who was living above where her family was living. “I discovered a whole new world of artists, dancers and specifically Brazilian music. He was not a teacher, but his world was a teacher.” Tsarouchis worked a lot in theater doing costumes and scenery for the Dallas Civic Opera, the Royal Opera House, the Ancient Theater of Epidaurus, and La Scala. He used to take his young apprentice around to all the shops to buy things. “He was like a philosopher, like a Socrates. The most important things I heard from him came just before crossing the street; he was terribly afraid of crossing the street!”

With Tsarouchis, the young artist worked on Norma (1960) and Medea (1961) featuring the Greek soprano Maria Callasat the Ancient Theater of Epidaurus. “Hearing Callas at all the rehearsals, I learned every word of Norma by heart and it inspired me very much.” Her first independent commission arrived a little later at the age of 21 when Greek actor Taki Horn asked her to design the sets for his stage adaptation of Gogol’s Diary of a Madman (1961). Horn said to her, “You are a Tsarouchis student and I want you to do all the costumes for my next play.” She replied, “Alone?!’ and he looked at her and said, “If you don’t take occasions in life. Forget it! You are going nowhere.” And so she did, driven by an immense curiosity for art and theater.

More commissions followed for the École des Beaux-Arts graduate and student of Austrian artist Oskar Kokoschka. She was asked to design costumes and sets for Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night at the National Theater in Athens (1973), for Niki de Saint Phalle’s film Un rêve plus long que la nuit(1976), and Sophocles’s Electra (1983) at the Ancient Theater of Epidaurus. But one good day she decided that painting would become more important. “I must say I gave up theater… I love everything in theater. I love the atmosphere. But I couldn’t stand shopping — terribly trying and time consuming.” The theater, though, never gave up on her, and like a wandering spark she consistently worked with the Greek actress Irene Papas to design the costumes for Euripides’s Trojan Women (2001) in Valencia and Euripides’s Hecuba (2003) in Rome.

Another painting in the studio portrays a woman with a red floral crown, her daughter Alexandra, with the artist Rob Wynne. Karella lived with her family in New York for fourteen years after having lived in Paris for six. “Being an artist gives you tremendous freedom, but this part of having a family, having children and having a structure, I needed that.” Every morning she used to take her old-fashioned, second hand, gold Cadillac and drive downtown to her studio. Her husband would be at home writing. “Soho was empty; there were still rugs hanging out of the windows.” She and Jean Michel Basquiat even shared the same assistant. “Basquiat used to have sandwiches in front of my studio in Spring Street. Alex Katz was next door. Julian Schnabel started his plate painting… everybody was wide open and I think that’s what gives New York the energy that it has.” Gentle, accessible and generous, she remained close to that New York mentality and was surprised to see how in Europe artists are much more guarded. “It’s not open house. It’s not come and see and I will show you how I do. There are little chapels of people with their people around them.”

Currently her mind is set on furniture and how the sculptures she has designed in the past can be turned into utilitarian objects. Her French assistant comes along and together they put photos of her sculptures on the wall. “I have always loved working with assistants. I find the interaction very important.” Interaction between artists is also important to her, and she credits her artist friend Niki de Saint Phalle with enticing her into sculpture by inviting her to design a sculpture for her Tarot Garden in Tuscany, Italy. “Niki asked me one day, ‘Don’t you ever feel like doing sculptures?’ I said, ‘Yes, but I am a painter!’ and then all of a sudden the idea got into my head. At that point I was painting chairs and I said there is nothing better than to make a three dimensional chair. That’s how the whole thing started. I started with chairs of a kafenio, café chairs really Greek.”

Every artist has a basic theme that he is all about. It comes out in all sorts of ways and possibilities. My basic theme is where we go from here.

Marina Karella

One of the sculptures pictured on the wall, The World (1984), is a chair, but it is seemingly covered in fabric with one arm decorated with a pearly white sphere carved in resin. Silver Tower (1999), cast in bronze, hides a gold pearl within its folds, and the Fountain (1999), also cast in bronze, creates the illusion liquid and fabric are one. Thus, in different ways each demonstrates her interest in the draping of objects. “The cloth is a bundle, it unfolds and you breathe. Every artist has a basic theme that he is all about. It comes out in all sorts of ways and possibilities. My basic theme is where we go from here.

Three other photographs reveal different explorations. Retour au Commencement (1994), Le Monde est un Grain de Sable(1994) and Epinikion (1994) are vertical, streamlined, totem pole-like sculptures that have an almost primitive aspect. Karella associates verticality with the urge towards the infinite. “It’s a Brancusi idea.” Nevertheless, she points out small elements on top of the sculptures. “All the things I put on top are like travellers. I have little objects on everything I have done” including, out on the terrace, the sugar bowl topped with a horse playing a guitar. “A cow that looks at the moon, a bird, a horse … A slight interpretation without forcing interpretation.” The pieces in the photographs will be given new life as her sketches indicate. “I feel totally rejuvenated to be doing sculpture again. This I am making into a bench,” she says showing Le Monde est un Grain de Sable turned parallel to the floor.

A small sculpture on her drawing board combines elements of the pieces in the photographs. The draped chair with a cat’s head perched atop it is stately with an almost Egyptian feel to it. Without a moment’s hesitation she says, “This is a maquette and I want to produce them in Greece. It’s going to be made from plastic.” She had been walking down Madison Avenue when all of a sudden she saw “this absolutely strange little cat object” looking at her like that, and she said to herself, “Oh my God that’s what I want to capture!”

Back on the terrace as the summer light begins to ebb, thoughts turn to Greece as inspiration for her work. Writer Vincent Katz, son of artist Alex Katz, worked with Karella as a studio assistant. He has written of the importance of the Greek influences in Karella’s background. Her series of altars vested with white linen evoke the hagia trapeza in Greek churches. The color white she uses so often is seen in the whitewashed houses of Patmos. Her paintings of dark Greek cafes (kafenion) bring to mind memories she has had since she was a child visiting the Greek countryside where she would pass in front of the cafes filled with men while the women stayed at home. Her proportional sculptures are related to Cycladic figures. Karella adds to this list. “In all the portraits I do I always have in mind the classical ideal in Ancient Greek Art. It is timeless. But also I am very attached to the island. Since always, I have been thinking of and contemplating the Greek landscapes.”

Patmos, 2016. All photographs and text © 2016 by Alexia Antsakli Vardinoyanni – www.artflyer.net