It all started with a drawing that American artist Kiki Smith made seven years ago of the long and wandering Hydra, the sea serpent in the sky, and its adjoining constellations Corvus (crow), Noctua (owl), Crater (chalice), Sextans (sextant) and Felis (cat). Smith turned all these celestial elements to symbols for Memory, the installation she conceived for Deste Foundation’s satellite project space, a former slaughterhouse on the Greek island of Hydra. “There are about four or five different groups of work in the show; whether or not they fit together, I can’t say,” says the artist.

The celestial Hydra may be named after the Lernean Hydra, a fearsome serpent with nine heads that Hercules had to defeat as part of his twelve labors. In the sky it is depicted with only one head, however, presumably the immortal one. As Smith thought of ways the myth could translate to the site, images of Capricorn another mythological and starry creature came to mind. Capricorn with the head and upper body of a goat and lower body and tail of a fish comes in two different variations in Smith’s installation. On the roof, the artist perched a bronze body of a goat and left its polyester fishtail, with her digitally-printed hand-drawn fish scales, hanging in a curve. “We put four safety pins. Then it opened itself to where it likes to be and then we sewed it,” she says as she adjusts the wire that will connect the tail to the body of the goat and make a symbolic amphibian.

Two more figurative Capricorns cast in bronze, half human and half animal hybrids, with a woman’s face (a self portrait), a woman’s chest, goat’s hooves and a mermaid’s tail, were installed in the stalls of the former slaughterhouse. One is mounted on the wall and another one is mounted between the bars that are used to separate the room in three compartments. “Originally, one was going to fit in the end stall and the other part outside of the wall, but they can’t put scaffolding outside this building because it’s too steep, so it moved here. It’s fine. You have ideas about what you are doing and then you get there and you just have to deal with what’s there,” she says standing on a ladder to inspect the highlights of the bronze. With her hand on the sculpture, the light blue constellation tattoos on her skin seem to spread onto the artwork as decorative bronze stars.

You have ideas about what you are doing and then you get there and you just have to deal with what’s there.

Kiki Smith

The snake appears not only celestially, but also on the island’s flag where it is shown wrapped around an inverted anchor with its head being bitten by an owl. To represent the owl, the artist created a small bronze sculpture and secluded it in what looks like the perfect hideaway inside the slaughterhouse. “At first I had the owl with its wings up and then I said no. But when I get home, I can make a mold for both positions. I like to keep changing it, like a paper doll. You can put this dress on and then that dress — animate them.” As she talks about all these different variations, it’s obvious how much pleasure Smith takes in the creative process. “You know as a person I’m not that fascinating. I basically like making things. It takes endless amounts of time to make things. So essentially I just work and I don’t even think that much. I have blind faith in what I am doing and then I don’t have to question it so much.”

Wood was the obvious choice of material to make the cast for the owl. Because her husband does a lot of wood cutting at their house in the country two hours north from New York City, there was plenty in the backyard. Taking pieces of wood and making them into the owl is an additive sculptural process. “It’s exactly how we [she and her sisters] made my father’s paper models. There was a shape, but then we just took them and taped them together. Just constructing something from nothing, rather than sculpting in the sense of being reductive like carving stone.” Although her father, artist Tony Smith, is often cited as a pioneering figure in American minimalist sculpture, Smith considers him an abstract expressionist. “It’s not minimalism. It’s not reductive in the slightest.”

Outside the slaughterhouse, she “wanted to make a waving to the sea, with the sea waving to the reflection.” So, she drew images of the smaller attendant constellations and printed them on white flags that fly from seven flagpoles installed on the route above the slaughterhouse. “I saw these flag poles based on masts of ships, that have a cross bar and three flags and I thought that’s nice, and you have them in the town as well.” Pushed out by the wind intermittently, the flags reveal a crow, a chalice, a cat and a sextant and reflect another Greek myth. Apollo was angered by the crow, who, while he was indulging on fresh figs, delayed fetching fresh water from a sacred spring for a ritual, and then blamed the snake. The god cast into the sky the crow, the snake and the chalice so that the snake could prevent the crow from ever drinking from the chalice.

On the lower part of each pole, two blue flags also fly in the wind – cyanotypes of photographs the artist took back in 2005 of the sun shining on the East River. “Last year one of my students showed me how to make cyanotypes which I haven’t done in about 30 years. Then I scanned them and made them into the flags. I wanted tons of small flags, but I did not mean to kill people working, because to put things into these rocks would be quite difficult.”

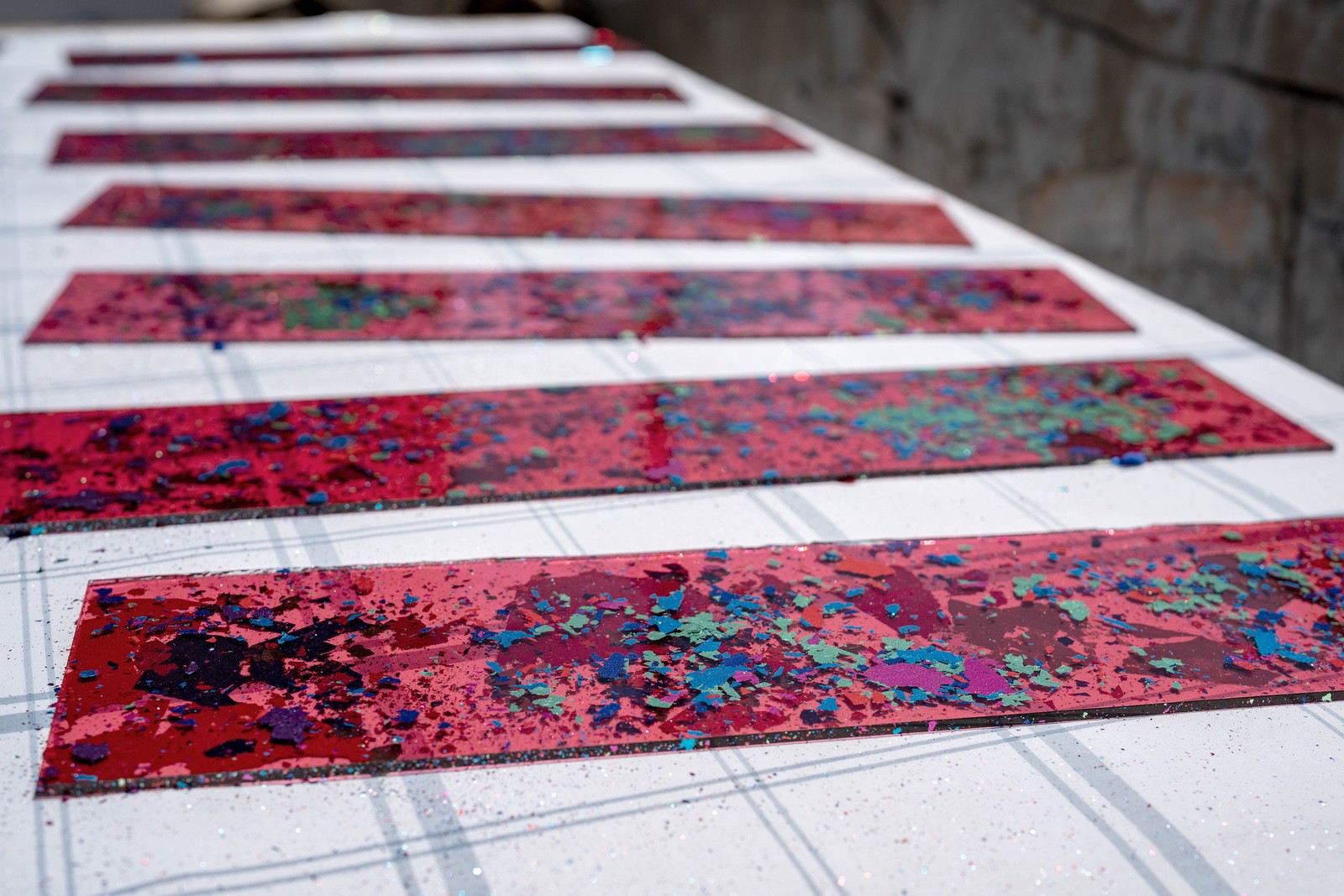

She transformed the slaughterhouse itself by replacing the clear glass windows with pink rubino glass. This striking stained-glass effect radically alters the interior as the light through the glass projects vibrant pink tones on the floor, wall and ceiling and immerses the visitor in a radiant glow. “I am actually very happy with it here, in this softness and how it looks from the outside when it’s dark.” Smith had several cases of pink rubino glass in Germany, the most expensive glass you can buy, but had no idea how to use it. “And then I thought it was a little bit like the blood of the slaughterhouse. I spoke to one woman and to Dakis [Joannou] and they said they remembered the blood in the sea when they were slaughtering the goats.” Also tapping into her fantasy to play with the rich history of Byzantine culture and all the light that’s made from glass mosaic, she applied a Japanese dyed gold leaf to the glass in Hydra. While the ethereal light comes through into the building, “on the outside you do have this kind of church window with the gold reflecting back.” A wide and shallow bronze offering basin, or crater, to represent the chalice, in the center of the room adds to the religious iconography. Filled with water, at a certain time of the day, it reflects the pink window. She is pleased with this effect. “It’s animating the blood or just life.”

To emphasize the sacrificial element of the basin, she made a cast of goat organs because they are “what slips away intothe sea.” Originally, she thought to present them separately as shields and hang them on the wall, but not happy with the result, she put them together. “I don’t know if it’s Greek; it is certainly Roman and probably Greek before, using organs in divination. I saw bronze and stone sculptures of livers when I was young. It made me a lasting impression on me.” Until the Hydra installation, Smith hadn’t done anything with organs for twenty years. Now that she lives in the country, she’d rather look at hummingbirds and different animals. “I go, ‘oooh,’ what does that mean!?”

The cat constellation doesn’t fit into myths as do the other adjoining constellations, but in this “synagogue of different animals” she thought it would be nice for children to have “things that entertain them or secrets that perhaps no one else sees, but they do and are excited.” Some of those little things are her old “strange” sculptures of cats, made of wood. “On the one hand it seems incredibly stupid and on the other hand what can be more profound than a cat?” She also placed a little donkey on a steel beam, a small shiny crow on the outside of the building – Apollo’s sacred bird in Greek mythology originally had white feathers – and made coloring books, “Capricorns like mermaids on the rocks, because I think it’s nice if kids make something out of it. It’s a big thing to come out here.”

In search of navigational tools to complete the constellation’s inventory, she discovered a sextant and a lighthouse at the Museum of Hydra and decided to copy loosely the lighthouse. She made a small version for the slaughterhouse and will make a bigger one at home. “These two big Fresnel lenses look like eyes, or like a snake looking at you.” Placing two beeswax candles in the eyes of the lighthouse, she is happy with this sort of physical manifestation of the spiritual world.

Her experimentation with lenses led her to install one more object outside the slaughterhouse. Like the lighthouse, this one also has eyes but eyes that are more like an owl’s than a snake’s and are meant not to stare with but to be looked through. From a piece of wood that naturally formed two hills, she transformed a torso into a face, creating another hybrid figure. “On the outside they were like breasts or bosoms and then I finished that piece and I thought I would make it with lenses. Instead of being bosoms, being eyes.” Looking through those eyes, we have to study an inverted view in which land and water are above the sky, for what interests Kiki Smith is the “horizon and where the sky and the earth meet, or the sky and the sea meet, that space where things touch one another.”

Hydra, 2019. All photographs and text © 2019 by Alexia Antsakli Vardinoyanni – www.artflyer.net