From her office on the top floor of a former cereal factory warehouse on the banks of the Tagus River in Lisbon, Joana Vasconcelos coordinates all her studio’s activities. Below her, on the ground floor, two lions covered in crochet lace, assisted by some of her tallest sculptures, guard the entrance, distracted neither by the aroma of fresh coffee emanating from the refectory nor by the noise of men welding and cutting metal in an engineering workshop. Reached by a ramp, the office floor —architecture, finance, production and the artist’s foundation Fundação Joana Vasconcelos —supports the atrium a stairway above it. Here different workstations ranging from textiles to embroidery, to sewing and even mechanics edge the enormous open space used as a production and testing facility for large-scale works. A skylight allows the sun to shine directly onto the floor or cast animating shadows.

Her office is as colorful as her spirit. Little playful narratives are hidden everywhere. For example, a Fernando and Humberto Campana Cartoon Chair converses with an Arne Jacobsen Eggnetic chair handmade with her trademark wool crochet. “Recently, I had to redo it because my cat had put his claws in it,” she says as she sits at her desk to draw. Across from her desk is a wall of inspirations. A drawing by her 6-year-old daughter, two of her grandmother’s paintings, and the ceramic Rooster of Barcelos that inspired her monumental Pop Galo. Also on the wall is the logo of her company, a variation of the infinity symbol or of the number 8 that has particular significance for her. It is made with primary colors plus green to reflect the colors of the Portuguese flag. Vasconcelos was born in Paris and returned to Portugal when she was 3 years old. “I am a Portuguese artist; that’s who I am. Had it not been for the Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos), my parents would have stayed in France, and today I would have been a French artist.” A framed prototype near the logo illustrates the gossamer effect of the iconic Portuguese filigree jewelry ‘heart of Viana’ reinterpreted with red plastic cutlery, a unique technique she came up with and used in her Independent Heart series.

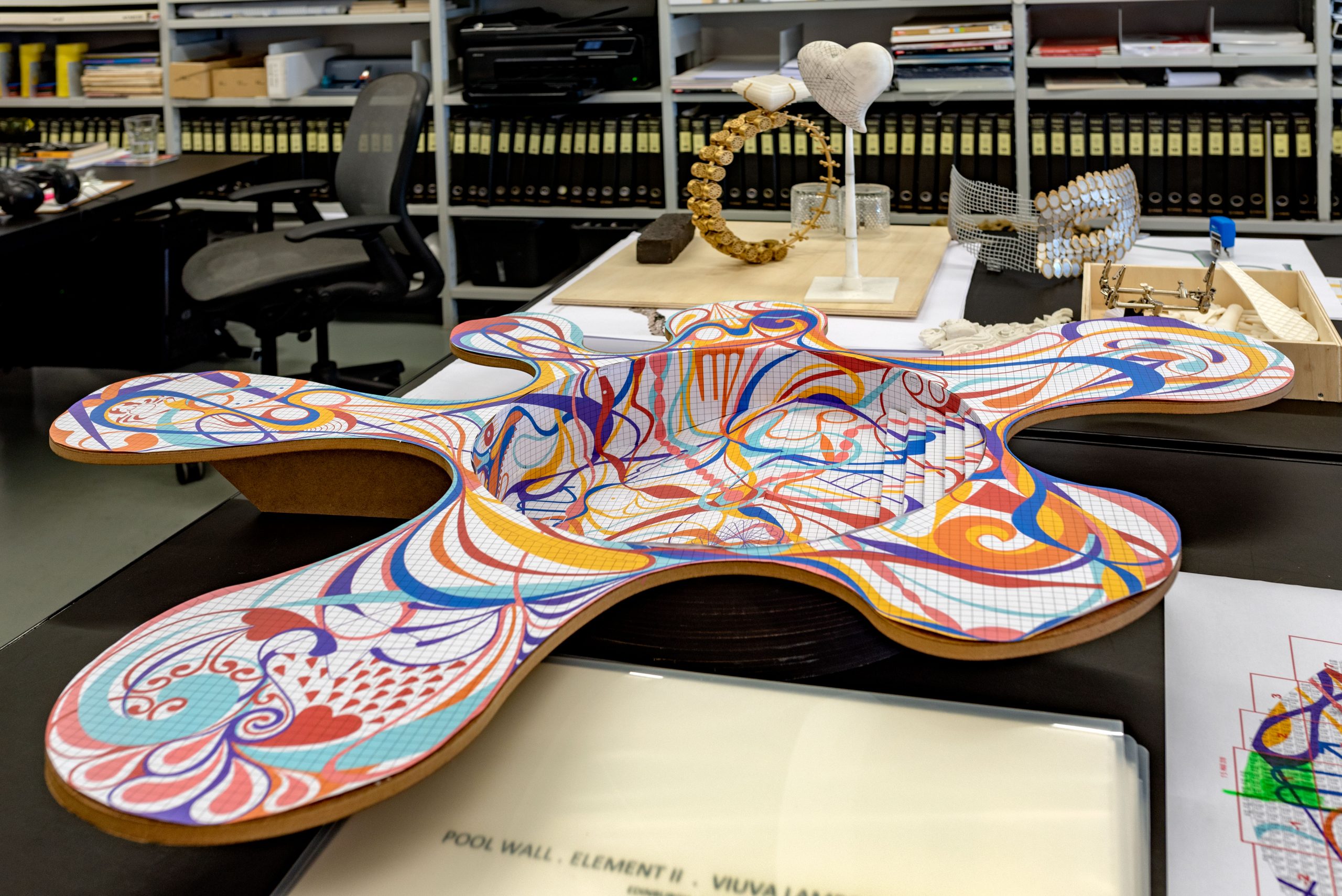

“I am trying to make a drawing exhibition. So, I go on and draw,” she says as she picks a blue Posca pen. There is nothing messy about her drawing. In this abstract composition, the lines are clean and precise. A composition of similar nature is featured in the design of the pool she is making for Jupiter Artland, a sculpture park in Edinburgh, which is also home to Robert and Nicky Wilson whose 17thcentury house is nestled in the middle of the 100-acre estate. The drawing prototype is in her office, while the 3D model is downstairs in the architectural studio led by Pedro Carvalho.

The pool, in the shape of a splash, is her first commission of this kind. “I had an exhibit in a sculpture park before, but I did not have to connect with the earth. I just placed the piece and left. This time, I had to adapt to so many new things and a family that has a collection of mostly English artists. Suddenly it became so private and personal.” Researching, Vasconcelos discovered that the park is laid on a ley line. “I did not know much. I went to study about ley lines and how building on this ley line was so important. It’s funny to see how all cathedrals are built in energy places.” She had done a large-scale installation of a glow-in-the-dark rosary for Fatima that is suspended outside the entrance of the Basilica of the Holy Trinity, and now she has found that the ley line there goes through Edinburgh. “I am doing this twice!”

For a different sculpture park, in Buckinghamshire, Lord Rothschild commissioned her to design a wedding pavilion in the area of the Rose Garden of Waddesdon Manor. “Every summer, they have all these visitors and do all these weddings and parties. And I thought there is no wedding without a wedding cake. So I started studying how the wedding cake is connected to architecture.” Finding a strong link between them, she came up with a structure that is an enlarged wedding cake and is even decorating it with creamy glossy tiles and rose-like ornaments. For inspiration, she keeps a picture of the wedding cake that was made for Lord Rothschild’s grandmother. “In architecture you have these small constructions that are not really for anything. They are just there. It’s about beauty. I am interested in these random spaces in the world that are not defined but do exist.”

While the heart, still under construction, is covered in white paper outlined with a grid for drilling holes to receive little LED lights, the painting behind it is completed and bold in color. It belongs to a series called Crochet Paintings and is made up of several different detachable capsules crocheted according to the artist’s indication of color, pattern, and thickness. The capsules are stuffed with a cushion filling to give them “life” and then are arranged like pieces of a puzzle on a wooden screen. The joyful mountainous landscape that results defies gravity and is framed by an antique-style frame made by The Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva Foundation. “Their frames bring you back into the past and project you into the future. They go both ways. We have this strong heritage of the Baroque in Portugal (barroco means rough or imperfect pearl in Portuguese) and I am influenced by it. I am a Baroque artist in the end.”

A similar crochet painting will be in her retrospective I’m your mirror at the Guggenheim Bilbao Museum opening in June 2018. Together with parts of a gold Cassetta wooden frame that will be nailed together, half a dozen crocheted and embroidered pillows of various forms and sizes lie on the floor, waiting for the artist to arrange them.

We have this strong heritage of the Baroque in Portugal and I am influenced by it. I am a Baroque artist in the end.

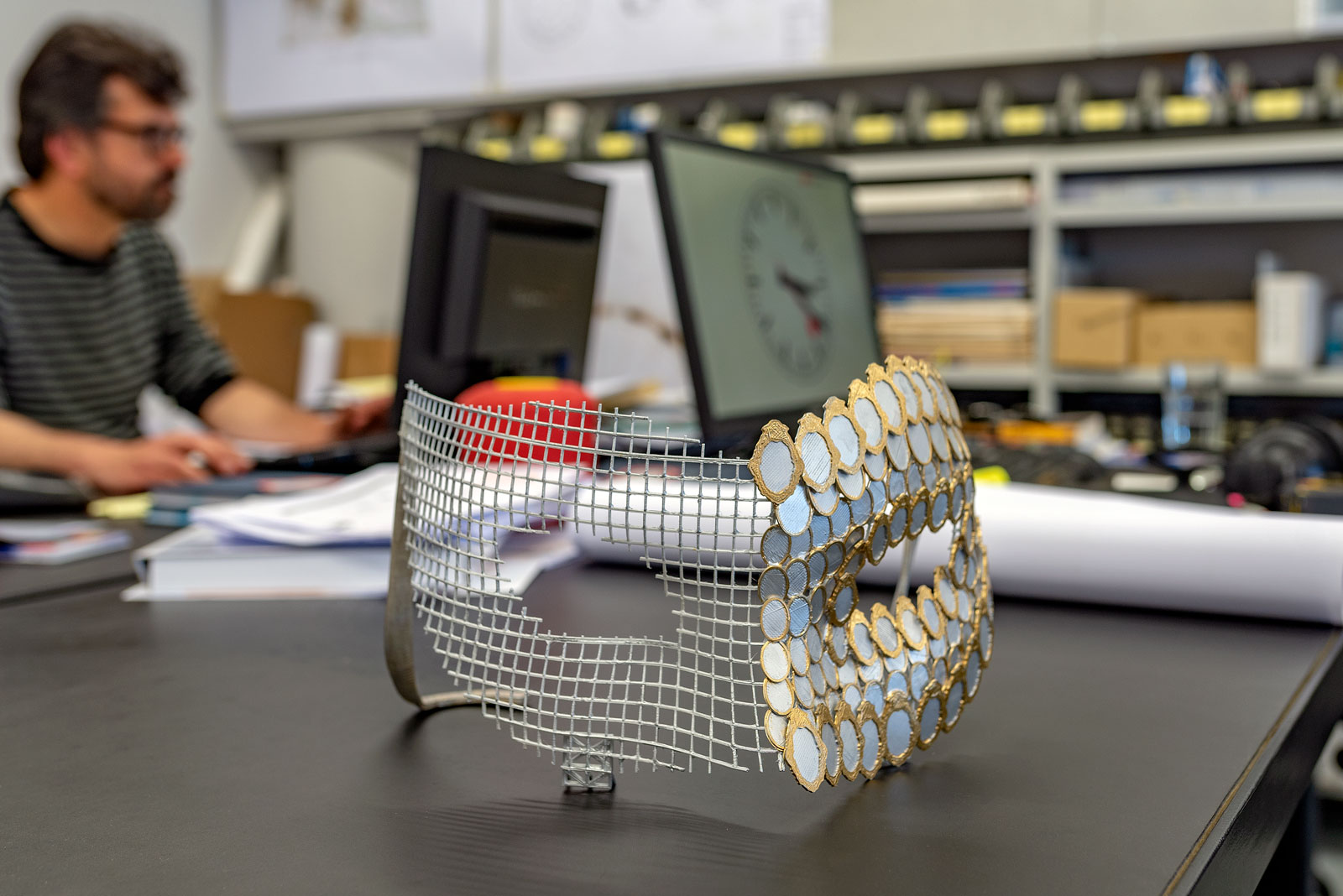

Joana VasconcelosThe Crochet Painting joins Solitaire (2018) and the Venetian mask I’ll Be Your Mirror (2018) in the group of new pieces made for the retrospective to be displayed together with the artist’s most iconic works. Both new and old pieces illustrate how Vasconcelos likes repetition as a means to abstraction and how the seemingly banal can be transformed into something luxurious. “I do a kind of sculptural pointillism. Repeating the dots. Suddenly you are not looking at the object, but to the object created by the dots.” A cascade of glistening tampons becomes an imposing chandelier in A Noiva (The Bride, 2001-05). Stainless steel casserole pots and lids become a seductive pair of heels Marilyn (2009). Irons become a robotized fountain in her Full Steam Ahead (2012-2014), which performs a kinetic choreography that took three years to produce. Wheel rims and Portuguese crystal whiskey glasses will create an engagement ring, the Solitaire (2018), and mirrored wooden frames will form a monumental Venetian mask, I’ll Be Your Mirror (2018).

The repetition in each of these pieces also serves to create a rhythm into which she embeds a conceptual riddle. A Noiva, the piece she declares is her soul, illustrates the core of her feminine manifesto and her desire to shed light area that are the dark corners of women’s existence. “In some places of the world, they tell young women that tampons can be dangerous for your health and can take your virginity, which is crazy. It’s not allowing us women to be free and be aware of our own bodies. There are a lot of things to be done for women to have the same human rights, the same freedom to live their lives as they want to.” Marilyn reflects on how the contemporary woman juggles multiple roles. “In the past the role of women was very established. You would marry and have a family. It was quite simple and now it is very complex. We cannot look back to our mothers and grandmothers to establish a pattern; the pattern was broken. We have to recreate it.” The Solitaire merges seamlessly what men want, “fast cars and whiskey,” and what women want, “a diamond ring.” The I’ll Be Your Mirror mask, “a symbol of European tradition” investigates the psychological effects of disguising, hiding or seducing. “Mirror is a material, very secret and particular, almost magical. You are also going to be part of the piece and that is quite interesting. It’s going to include you physically.”

A similar effect of concealing identity occurs in her work with the ceramics of Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905). Vasconcelos “adopted” eleven of his pieces, primarily animals that generate discomfort or fear like wasps or snakes, and gave them a second skin in crochet. In doing so she helped save Pinheiro’s Caldas da Rainha factory from closure. “I feel glad that I could be part of that process and keep his work alive. In the future, if that happens to my work, I hope that someone will look into it and say it’s worthwhile to keep this thing alive.” One room in the studio, dedicated to dressing up the animals, contains boxes filled with unique crochet lace designs made by small studios in the Azores and in the Alto Alentejo region of Portugal.

Some of Bordalo Pinheiro’s animals are oversize and trigger a sense of awe. Similarly, the dominating size of Vasconcelos’s textile creatures, the Valkyries, is worthy of awe. The artist wants us to think of these creatures as protectivespirits, echoing the female deities in Norse mythology, who fly over the battlefields and pick up the brave warriors to bring them back to life and work for the gods. Since 2004, they have constituted an open series in a vast array of materials, colors, and patterns. Their balloon-like bodies with tentacular forms create spectacular new architectural environments and take on a number of different personas: a spider-like Enxoval (2009), a flying Mary Poppins (2010), and a gloomy Victoria (2008). For HDA Var (Hôtel Départemental des Arts du Var) in Toulon, Vasconcelos is making a Valkyrie with male suits. “I had this collector that wanted to give me all the suits of his father, a collector too. And then I thought I should do this personality of a woman who likes to dress in a tuxedo. We are creating a world so expanded that we can be whoever we want. If we want to be dressed like men, why not?”

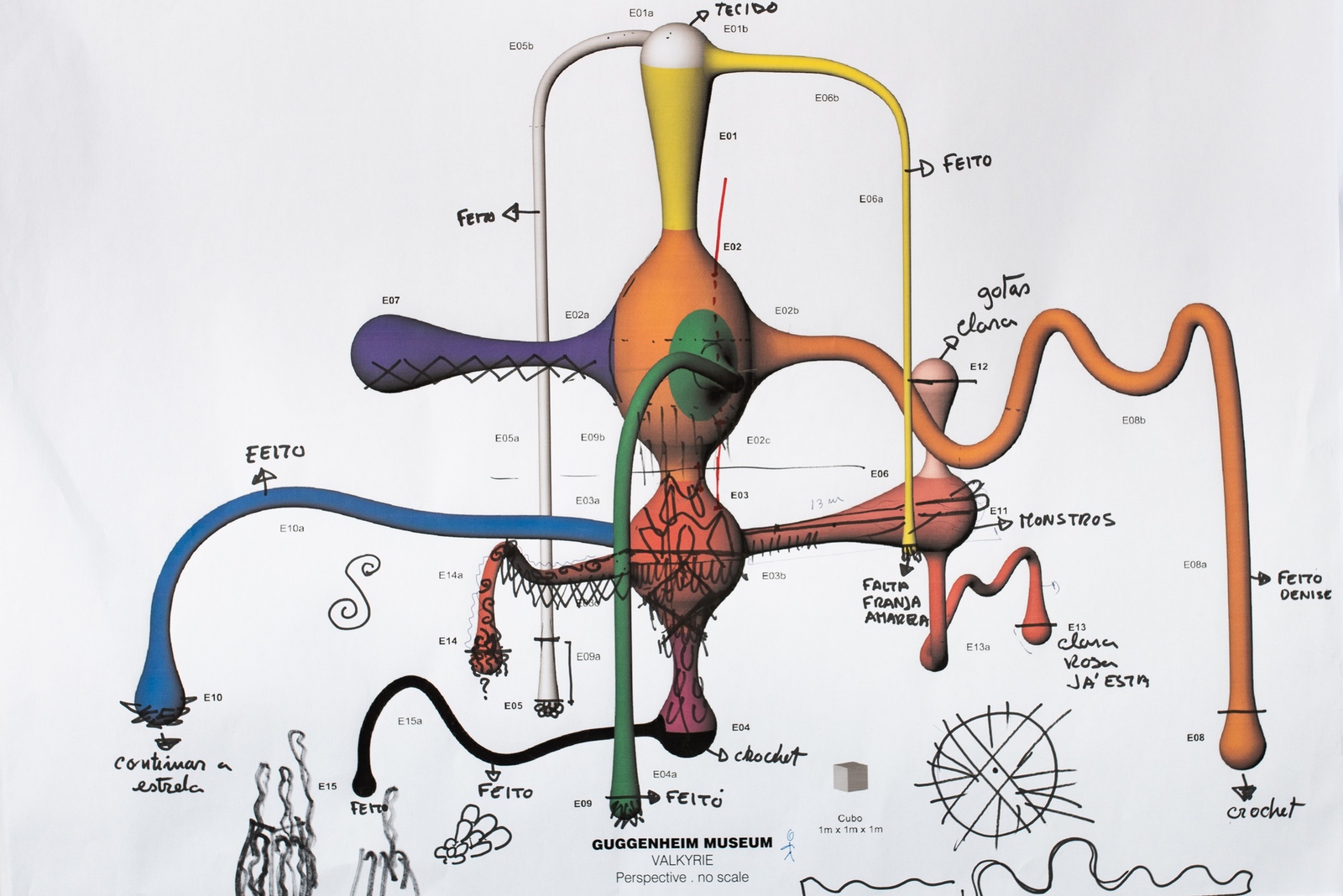

A rendering of the Guggenheim Bilbao Museum Valkyrie Egeria with notes of the artist.

Different ornaments to decorate the Valkyries from the artists’ travels abroad as arranged in the workshop.

Part of the Valkyrie that will presented in Toulon, made with ties.

Decorative pearls.

All Valkyries are made of several independent modules and put together with zippers and fixing points. They have an inflatable core so that when machines blow air into them, they grow. Valkyries are about stretching and transforming space, filling the architectural void and establishing a dialogue. “The first level of connection is with the building. It connects with the curves and the light.” Valkyrie Rán is a permanent installation 50 meters long, specially designed for ARoS Museum in Denmark to go across the five stories of the building, but it mutates. “We made it adaptable to their needs. You can take off some parts of it, but always have some part of the work.” The Guggenheim Bilbao Valkyrie Egeria will be 35 meters tall.

Part of another Valkyrie has been brought in for testing. Workers unfold what looks like a pile of huge pink, purple, salmon-colored patterned ropes. Some have a changeable mother of pearl appearance, some sparkle with sequins, and some are decorated with lights. The braided channels splitting and rejoining make the Valkyrie look like a rippling stream until pumped air begins to fill the core, which slowly starts to take shape. As Vasconcelos finalizes the details, some of her gestures reveal that this is the happiest stage of a commission for her. “When you install, you know you are getting to the end. I like the moment where we are now. The dynamics of it. There is a lot going on — problems to solve and things to define. The process is the most interesting moment for me. In the prep I am a little bit bored. When it’s happening, its super amazing.”

As of now the Bilbao balloon is still tethered to the ground, but fully inflated and elaborately decorated, it will eventually rise and gracefully float, as the drawing indicates, in the Guggenheim’s main atrium. “Gehry left an amazing space full of angles, dynamics and curves, and I am inhabiting it in a way. I feel like an opera singer that is filling up the opera house.”

Lisbon, 2018. All photographs and text © 2018 by Alexia Antsakli Vardinoyanni – www.artflyer.net